The geometry of movement — IMO Gallery

IMO Gallery / Kopernika 1 / Stary Sącz

Exibition: "The geometry of movement" / 26.10.2024-19.01.2025

opening: 25.10.2024 godz. 18.00

curator: Agnieszka Tes

Artists:

Tamara Berdowska / Sławomir Brzoska / Mieczysław Janikowski / Juliusz Kosin / Michał Misiak / Kinga Nowak / Katarzyna Rumińska / Katarzyna Tretyn / Victor Vasarely (grafika) / Apoloniusz Węgłowski / Olga Ząbroń

The geometry of movement is not only the inspiration for the exhibition at IMO Gallery, but also the principle of its arrangement, which dynamises thinking about the whole, the artworks in space and their interactions. A principle that has largely determined the choice of artists, which present a variety of approaches, ways of thinking and using the ‘language of geometry’. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the geometric current in abstract art has undergone transformations, initiated various, often contradictory concepts, been a kind of medium for going off the beaten track, combining the universal aspect with that which corresponds to the spirit of the times. Euclidean geometry, with its use of figures on a plane and creation of two- and three-dimensional spaces, provided the tools for this. It allowed contact with the sphere of the archetype or idea, ordering reality, transcending the variability of sensory impressions and perceptions, transporting the mind into meditative experiences. The new non-Euclidean geometries developing from the 19th century onwards, taking into account the existence of n-dimensions and curvatures of space, also provided an additional challenge and impetus.

Aspirations of evoking movement were present in the geometric abstraction from the beginning of the 20th century, appearing, for example, in the famous suprematist compositions of Kazimir Malevich, the neoplastic works of Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg or in experiments conducted at Bauhaus. ‘The aeronautics craze’ mentioned by Vasily Kandinsky, the first aeroplanes, the concept of the fourth dimension, and finally the rhythms of urban metropolises inspired experiments with the still inexhaustible potentials of geometry. The second important moment in which these tendencies manifested themselves was in the mid-1950s with the groundbreaking exhibition Le mouvement in Paris (1955). One of the leading figures of this change was the precursor of op-art, Victor Vasarely, a Hungarian settled in Paris, who began to formulate ideas of virtual movement and introduce optical illusions into his art. His compositions played with the destabilisation of regular patterns, he used inversions of figure and background and explored the mechanisms of perception, creating on a flat plane the impression of vibration, rippling, swirling, changing dynamics, concavity or convexity, etc.

The exhibition at IMO Gallery brings together twenty prints from the 1960s, 1970s and late 1980s by this well-known artist. They constitute a kind of starting point in the visual ‘narrative’ of the exhibition space, interacting with the works of Polish artists, clearly demonstrating the diversity of approaches to the problem of movement expressed by abstract means. However, while Vasarely’s art actually closes itself in visualism, not pretending to express deeper levels of experience, most of the presented artists of the domestic scene consciously go beyond mere formal-perceptual relations, revolving around variously conceived meditative states (M. Janikowski, T. Berdowska, S. Brzoska, M. Misiak, A. Węgłowski, O. Ząbroń) or by including other issues (artists of the young generation: J. Kosin, K. Rumińska). The metaphysical orientation of the geometric trend in Poland, atypical on an almost world scale, was noticed by its outstanding propagator Bożena Kowalska. This tendency is already present in the art of Mieczysław Janikowski, who in the 1950s, having come into contact with Vasarely’s art, said: ‘For me, the unrivalled master of the visual side is the Hungarian, settled in Paris, Vasarely. Unfortunately, he despises content, that is, all that is in a painting unnamed for its undercurrent and inner meaning’ . Inspirations by the innovativeness of Vasarely’s works on the one hand, on the other, a subtle contemplativeness, alien to the precursor of op-art, can be seen, for example, in the three canvases by Janikowski (from Michal Molski’s collection in Poznań) shown at the IMO.

Movement combined with a metaphysical element coexists in the visually strong canvases of Apoloniusz Węgłowski, whose thinking on abstraction was shaped during many years of contacts with the eminent figure of Stefan Gierowski at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. In these works, both touching on the symbolic sphere and rich in formal layer, the carrier of movement are characteristic, as if laser-like beams of colour or geometric rhythms drifting/floating in space. The iconosphere of contemporary science and the phenomena of nature also provide an interesting context for their reception. Tamara Berdowska, on the other hand, evidently avoids all associations with the visible world, moving even more clearly towards the realm of pure ideas. In her spectacular, usually concentric, multi-layered arrangements, the artist activates the potentials of movement by operating positive-negative combinations within narrow ranges of colour. In doing so, she makes use of oppositional effects of expansion and contraction, optical ‘suction’ or swirling, which she realises both on the flat surfaces of the canvas and in reliefs and spatial forms made of plexiglass or foil. Unlike Vasarely, however, the Polish artist does not focus on perceptual illusions, consciously touching on the archetypal and energetic aspects of the image.

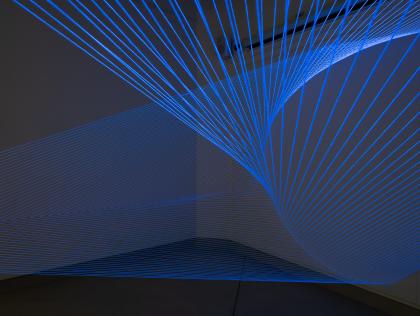

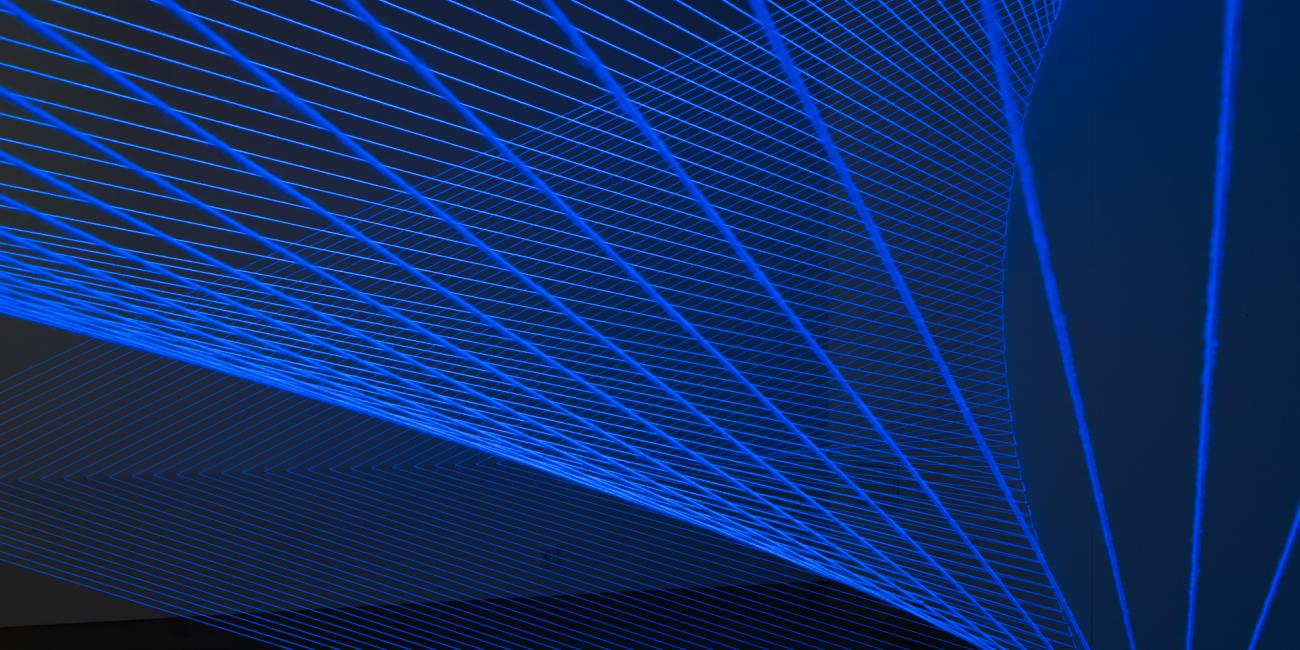

At the ‘Geometry of Movement’ exhibition, one of the means of expression on display is the line. It is the basic material in the works of Sławomir Brzoska, Michał Misiak, Katarzyna Tretyn and Olga Ząbroń. In fact, all the artists from the Polish scene mentioned so far have in common the practice of a kind of meditative creative process, a particular predilection for structures and the speculative-constructive aspect, and at the same time an openness to the creative intuition. In the case of Brzoska’s installation ‘Phainomenon, or the Moon over Stary Sącz’, prepared especially for the IMO, a sense of movement is created through the interference of lines in space optically transforming with the change of point of view. Starting from the archetypal circle, these interactions transform into the realm of non-euclidean geometries and induce the experience of potential multidimensionality. Tretyn’s ‘Time-space’, on the other hand, sets the circle in motion, as it were, through regular rhythms and tunnel-like runs of silver thread ‘dissected’ between perpendicular plexiglass panels. The juxtaposition of the lines interpreted in three dimensions with those appearing on the flat surface of the painting seems interesting. In the large-format compositions of Misiak’s ‘Frequencies’ series, the structural diversity is inspired by, among other things, contemporary music. As if waves and vibrations of sound, spread and converge on their monochrome backgrounds. Ząbroń, on the other hand, who has a predilection for delicate, hand-drawn ‘stitches’, prefers only minimal modifications of linear arrangements. In the works presented at the IMO, grouped in pairs, the painter goes beyond the limitations of traditional quadrilateral canvas formats in favour of ‘shaped paintings’, thanks to which the form gives the impression of opening up towards/inserting space.

In the artistic configuration created, it is worth noting the distinctive difference in approach of the three artists. Kinga Nowak approached non-figurative language from the side of representational art and observation of the natural world, which she has practised for many years. In the two spatial objects selected for the exhibition, based on the figure of a triangle and a rectangle, which, by the way, perfectly harmonise with the other works, a sense of dynamic balance and ambivalence of form, which arise depending on the handling of colour or shifts in perception perspectives. Juliusz Kosin, on the other hand, a painter of the younger generation, proposed three premiere canvases belonging to one series. Using a reduced language of geometry, he translates various historical chess games, from Napoleon, the Polish inter-war chess players, Marcel Duchamp and Kasparov to duels between artificial intelligence and a chess engine or a human being, into black-and-white (or possibly white-only) linear courses.

The works of Katarzyna Rumińska, an artist who also moves freely in the area of digital media, experiment with greater formal richness, a variety of shapes and textures, as well as three-dimensionality or kinetic effects produced by means of in- stalled devices. However, the young artist does not stop at the visual experience, aspiring to combine geometry with a message conceptualising (inter)human experiences and emotions. Interestingly, her works in terms of colour and composition proved to correspond intriguingly with the late prints of the Hungarian op-art pioneer.

The exhibition created at the IMO Gallery, by problematising the issue of movement in contemporary examples of geometric art, seems to make it clear that the purely perceptual qualities of visualism, the related psychology of perception and the handling of optical illusions initiated after the Second World War by Vasarely, are aspects that hardly occupy the artists presented at the exhibition anymore. Obviously, phenomena that were considered innovative in the last century are now

‘digested’, existing in the layers of consciousness, but not necessarily directly animating the creative imagination. Now one can observe the fusion of the problem of movement with processuality and its meditative dimension, the extraction of energetic/ spiritual or musical aspects of geometry and the maintenance of a speculative curiosity about the potentials of form, figure or line, appears significant. The presence of younger artists, on the other hand, indicates the emergence of unexpected areas of inspiration leading to fresh artistic solutions within the timeless language of geometry.

Agnieszka Tes, curator

1 Por.: L. Gamwell, Mathematics and Art. A Cultural History, Princeton University Press, Princeton, Oxford 2016, s.151-156; L. Dalrymple Henderson, The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art, revised edition, MIT Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts), London 2013. Geometrie te wywodziły się z ustaleń Carla F. Gaussa, Jánosa Bolyaia i Mikołaja I. Łobaczewskiego,

a także G.F. Bernharda Riemanna.2 W. Kandinsky, Complete Writings on Art, red. K.C. Lindsay, P. Vergo, Da Capo Press, New York 1994, s. 94.

3 B. Kowalska, Język geometrii – półwiecze przemian, Mazowieckie Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej „Elektrownia”, Radom 2016, s. 31. Autorka słowa te odnosi przede wszystkim do nurtu abstrakcji geometrycznej.

4 J.B., Rozmowa z Mieczysławem Janikowskim, „Życie” (Londyn), 1956, nr 43 (21 października), s. 11, [za:] M. Piłakowska, Linia prosta przeciwstawiona linii krzywej to już jest dramat, więc po co malować więcej? Kilka uwag o twórczości Mieczysława Janikowskie- go, [w:] Mieczysław T. Janikowski. Medytacje euklidesowe, katalog wystawy, Galeria Piekary, Fundacja 9/11 Art Space, Poznań 2021, nlb. Por. też: J. Starzyński, [Wstęp], [w:] Mieczysław Janikowski, katalog wystawy, Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, Łódź 1974, nlb.

curatorial text: Agnieszka Tes

photos: Marek Błażucki